Canberra: The view overlooking Capital Hill from Mt Ainslie is hazy. Parliament House is barely visible, sitting under a blanket of thick smoke.

Born and bred Canberran, Matti Collins, assures that the strange smell in the air is a result of bushfire – not the ACT Government’s recent legalisation of personal cannabis use and cultivation.

“It’s been decriminalised since I can remember,” he says. “As long as it was outdoors we were always fine, to a certain amount.”

The alignment of the city might give the impression of monitoring a political experiment. Described as a laboratory of democracy, Canberra has indeed built a reputation for implementing policies that prove controversial when considered by other jurisdictions.

Originally, the 1992 cannabis decriminalisation scheme was on the condition that individuals kept 25 grams or less and grew no more than five plants. New laws increase the possession limit to 50 grams and set maximum plant numbers at a potential of four per household – but now it’s legal.

At first glance, an outsider might expect cause for cannabis enthusiasts to celebrate, but this is not necessarily the case.

“Honestly, my plans haven’t changed,” Collins says, laughing.

“I don’t think they’ve given it much forethought.”

Labor backbencher Michael Pettersson says his bill is drafted on as much pre-existing framework as possible, including possession thresholds and prohibitions on artificial lighting and hydroponics. The limits on cultivation methods stem from police recommendations.

Pettersson suggests revising whether the reasoning behind this advice is reliable at a later date.

“First and foremost, we want to make sure that we land legalisation,” he asserts.

Turning away from the smog-shrouded view of his city, Collins shakes his head in disappointment. Judging from his experience growing under decriminalisation, he sees the bill as ineffective, despite the fact that – unlike Commonwealth law – it recognises fresh-cut cannabis for being much heavier than when it’s been dried for consumption.

Somebody looking to harvest the allowance of 50 grams would have to cut about 150 grams of fresh cannabis from their plant. An increased possession threshold for “wet” produce is designed to allow for this process.

Collins feels these terms are unrealistic.

“You’re getting more than 150 grams off one plant,” he says.

Also, in terms of buying, selling and gifting cannabis seeds or products, legal uses and practices in the ACT still depend on illegal acts.

But unless police pay a visit after harvest, Collins maintains he’s “not really that worried”.

Working within these set legal possession limits is “just one aspect of the problem”, says Andrew Kavasilas, Secretary of the Help End Marijuana Prohibition (HEMP) Party. “If we’re going to start breaking these new laws, are people going to start going to jail?

“Is it, ultimately, the perpetuation of prohibition 2.0?” he asks. “What happens if my plants do grow too much?”

Senior Associate at Aulich Criminal Law, Charlene Harris, says that even the death of a plant could create problems by dropping leaves that exceed legal thresholds, “and effectively become an offence through no fault of the person growing it”.

These issues and conflicts with Commonwealth trafficking laws are destined for trial in court.

“It’s a grinding standstill,” says Harris. “It’s just completely unclear, what’s going to happen, at the moment.”

The visibility in Fyshwick is not much better. Brett Walker from South Pacific Hydroponics says his customers are talking to him about the situation on a daily basis, and are often unaware of what changes have actually taken place.

“Basically, they’re allowing you to go and grow a couple of plants outside,” Walker says. “But you don’t get any chance through winter.”

As Pettersson suggests, police advice informing the ban on “artificial” cultivation is soon due for revision. The first amendments that saw the initial passing of the bill included recommendations from ACT Minister for Mental Health, Shane Rattenbury, to remove references that distinguish between gardening techniques. These sought to recognise that the Drugs of Dependence Act 1989 should be focussed on the substance and quantity of cannabis, not the method of its cultivation.

The Standing Committee rejected these recommendations.

Police advise “artificial cultivation allows for the growth of stronger cannabis”, Pettersson says.

“As far as the potency goes, that depends on the genetics of the plant,” Walker argues. “You can grow that same plant indoors, or outdoors; in soil or hydroponics.”

When international marijuana culture first reached Australia, horticultural variety was, pretty much, potluck. People had no idea what they were smoking. When indoor cultivation gained popularity, people became selective with their crops – promoting growth of squat plants from central Asia that produced high levels of marijuana’s primary psychoactive, THC (delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol), and were suited to restrictive indoor spaces.

In those early days, cannabis seemed to be getting stronger because of selective breeding – not the gardening methods that the Australian Commonwealth currently classify as “artificial”.

“It’s not like hydroponic nutrients supercharge the plant’s effects,” Walker says.

ACT Policing also claim hydroponic cannabis growth allows higher yields. Indoors, this is fundamentally relative to the size of a growing space and the amount of electricity consumed within it – boiling down, basically, to how much lighting is used.

More often than not, when given the proper care, outdoor plants produce significantly larger quantities of cannabis than their indoor clones.

The ACT has set no limit on how large the plants can be. They can be grown simply on the condition they are inaccessible by children and out of public view. If they are alive and growing, the police have no right to make arrests, issue fines or confiscate the produce – in theory.

Walker says this might be okay, “as long as someone doesn’t come and rip it off”.

As conversation in the hydroponics shop drifts around the different products available to organic outdoor growers, a customer silently interrupts, presenting a photograph on his phone. It shows a bruised gash, twisting aggressively down the bald patch on someone’s skull.

It’s the archnemesis of any cannabis gardener: Theft.

“There’re people that are going to be jealous,” Collins says. “You’re growing really nice plants in your backyard and they don’t have nice plants.

“There will always be people who don’t want to do the work and get it for free.”

Risk of exposure to unwanted eyes or potential thieves can be eliminated by the security of an indoor garden – with year-round harvests possible. This could allow passage for users to almost entirely remove themselves from black markets. ACT Policing’s advice, to the contrary, warns this may encourage people to fill rooms full of cannabis, stimulating criminal trade.

“Restricted to one 1000-watt light, you’re not going to get a whole garage full,” Walker says.

“You’re going to get two square metres.”

Limiting the amount of cannabis produced is simply a matter of establishing a maximum amount of wattage, per household, that is dedicated to a growing space. He says gardeners would be far less at risk of exceeding set possession limits than with outdoor crops, “because you can’t grow five tonnes of stuff with a couple of lights”.

Founder and Medical Director of Cannadoc, Dr David Feng, says his biggest concern with people growing cannabis for personal use is that “they won’t be able to know exactly what concentrations of therapeutic cannabinoids are in their plants”.

Most varieties of cannabis used recreationally contain high concentrations of THC and low levels of CBD (cannabidiol). Feng says this creates risks, “as CBD has a modulating role in reducing adverse reactions”.

“Also, with home grown cannabis plants there is a risk of contamination with bacteria, fungi, chemicals and heavy metals, which can be harmful to your health,” he adds. “Therefore, I feel a pharmaceutical grade medicinal cannabis product is far superior.”

It’s a matter of quality over advocacy.

“Don’t get me wrong,” Pettersson admits. “There will be people who will self-medicate with the legislation we’ve introduced. I’ve spoken to very excited Canberra residents that plan to medicate legally. For the most part, they’re probably already medicating illegally.

“If you want to talk about marijuana as a serious form of medication, then I think it’s very important that we allow people to know what they’re putting in their body. People self-medicating with unregulated cannabis is not a particularly sophisticated form of medicine.”

Sophisticated or not, the reality now experienced in North America is just that. Recreational cannabis legalisation landed in Canada on October 17, 2018 – to mixed receptions. For better or worse, Canadians are now able to self-medicate using marijuana. Prescriptions are optional.

HEMP Party Secretary Kavasilas says this situation “is circumventing medical cannabis”.

In 2014, a study on barriers to medicinal access reported only about 7 per cent of doctors in Canada helped their patients obtain medical cannabis.

“But you’d still have to go to a dispensary to get it, not a chemist,” Kavasilas says. “No pot was ever prescribed out of a chemist in Canada – and it’s still not.”

Briana Vaags, from City Cannabis Co. in Comox, British Colombia, admits to often feeling like the manager of a pharmacy, yet sternly reminds that she’s “not a doctor”.

“It’s important to note that I’m coming from a recreational perspective,” she says. “That being said, we do get a lot of people that come through the door that are looking to treat this, that or the other, and we need to have a conversation with them about what their options are.

“They’re coming to us for help.”

Vaags serves many customers who are looking for THC and CBD oils to treat conditions such as insomnia, sciatica, arthritis and cancer. But the most common issue presented is chronic pain, especially from patients who want to try cannabis oils instead of addictive opiates.

“I’m not going to fault a doctor for saying they won’t talk to you, or me, or someone, about cannabis – because they weren’t educated on cannabis as medicine,” she says. “They don’t want to talk about it because they don’t know what they’re talking about.”

Vaags claims her customers want to try medical cannabis as an option in taking control of their own health and wellness – yet they are complaining that doctors won’t discuss options.

“Like I said, we’re very careful,” she says. “But we’ll have that conversation with them.”

One year after legalisation, results from Canada’s latest National Cannabis Survey show 43 percent of the most enthusiastic users – those aging from 25 to 44 years – still obtain their products from “grey” markets.

“The grey market is what we called the legal market, before it was legal,” Vaags says. “It was right on the cusp of legalisation.”

While the ACT Government’s move is far from a green light to retail cannabis markets, a lot can be learned from the past year of Canadian legalisation. Insight into issues such as supply and demand, or medical stalemates are examples.

Pettersson recommends keeping debates about medicinal and recreational use separate on the premise that “conflating the two does a disservice to both”.

The situation in Canada, however, demands these two discussions take place in the same forum. Legalising recreational cannabis without significant emphasis on researching its medical benefits is proving to destabilise the legitimacy of such research.

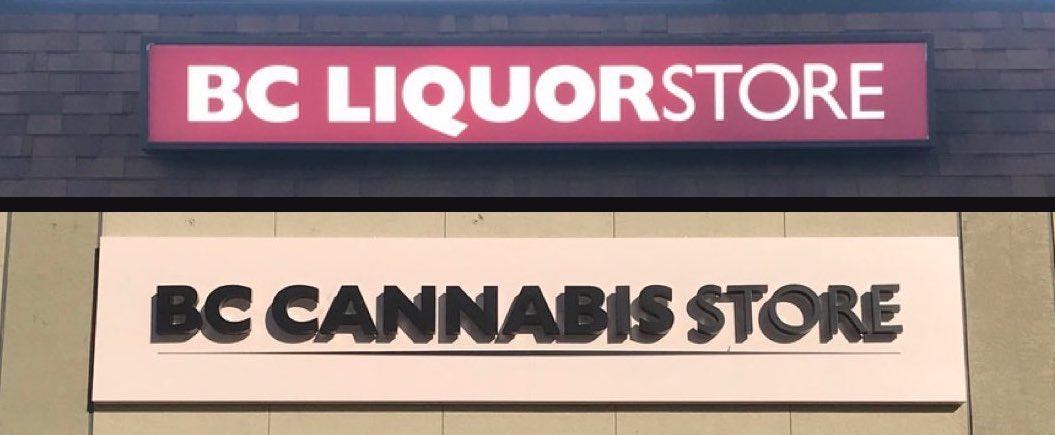

Similarly, the marriage of dominant liquor franchises to the cannabis industry promotes branding that does very little in ways of discouraging negative stigma.

In comparison, Australia boasts initially vague, difficult and expensive processes to access medicinal cannabis. Since 1992, the Therapeutic Goods Administration has authorised more than 28,000 applications for unapproved cannabis products for patients not defined as “seriously ill”.

But these numbers fail to reflect demand.

Australians continuing to rely on unregulated products is one of several specific reference points for the Senate Community Affairs Reference Committee’s report on current patient barriers to medicinal cannabis access.

While hesitant to join the recreational debate, Dr Feng sees legalisation in the ACT as a positive step forward with potential to destroy myths that give marijuana a bad name.

“It’s about as addictive as caffeine,” he says. “People don’t develop an immunity to it.

“The educational hurdles for doctors being aware of it – and the social stigmas around it – are probably the biggest barriers at the moment.”

The Senate Committee’s report is due by March 26.

Ingredients are in place and logic is brewing – Australia’s medical system may soon hope to taste outcomes. However, in comparison, the ACT’s cannabis “revolution” might be nothing more to Canberrans than a pinch of salt.

Pettersson admits users will generally source (now legal) goods “the way they always have”.

Illegally.

“For most people, growing plants is a lot of effort,” he says. “So, they will buy cannabis.”

If Australia followed Canadian footsteps, a potential cannabis market of over $5 billion could be subjected to similar distributions between legal and grey markets.

Kavasilas estimates Australian users consume “about a tonne per day”.

These projections are drawn using information from the National Drug Strategy Household Survey, which showed, in 2016, that 35 per cent of Australians over the age of 14 have used cannabis in their lifetime, with over 10 per cent in the last 12 months.

The ACT may not have set an ideal benchmark for legalising Australian cannabis, yet it certainly has made a clear statement – that pursuing recreational users or people with substance abuse problems is a waste of time.

As the summer smoke clears, Canberra’s new laws will settle for what they’re worth.

While Walker doesn’t expect to see new customers rushing in to buy all his fertiliser any time soon, he admits he sees the situation as “an advancement, because there’s at least some sort of talk and action being taken”.

However, Collins – a daily smoker – who claims a “healthy love for the marijuana”, believes his local government have initiated nothing more than a publicity stunt.

Asked if there’s any possibility of eliminating the black market from his life, growing under legal limits, he replies:

“Not a bloody chance in Hell.”

All images © Kal Omari

Share this: